I get dizzy just thinking about the film Man on Wire, about the high-wire artist, Philippe Petit, and his famous, unsupported high-wire walk across the Twin Towers of New York City’s World Trade Center in 1974.

Spoiler Alert: He makes it.

But watching the preparation and subsequent execution of this man’s quest was breathtaking work for me, even 50 years after the attempt and knowing the outcome of it in advance.

I found myself playing the quest out in my mind, wondering, what was Petit thinking? How did he mentally prepare? He’d walked a tightrope so many times, under so many perilous circumstances; how could he still be in the right headspace with new variables to consider — the shifting wind, the gathering crowd thousands of feet below, police officers in the wings waiting to arrest him the moment he returned to stable ground, curious birds? So many distractions.

And yet he orchestrated the stunt to end in one of only two possible outcomes: Complete the walk, or die.

My risk-hedging mind couldn’t grasp such a stark variety of outcomes. I wanted to add more options into the mix and urge Petit fruitlessly to make his way back to one of the towers by hooking to the wire and scootching back to the tower like an inchworm. But frustratingly, Petit wasn’t wearing a safety device.

The other aspect of Petit’s quest that struck me: His insistence on completing the quest to his satisfaction, even with the pressure to quit mounting. Petit doubles down when the stakes are highest, laying down on the wire at mid-point, where he is most visible, where the wire is most vulnerable to wind, eyes facing the sky.

I insist to myself that if I had been out on that wire I would have become too self-conscious; vertigo would have undeniably seized upon me; I would have noticed the crowd, the cops, the wind, the treachery of what I was attempting and condemned myself to fall.

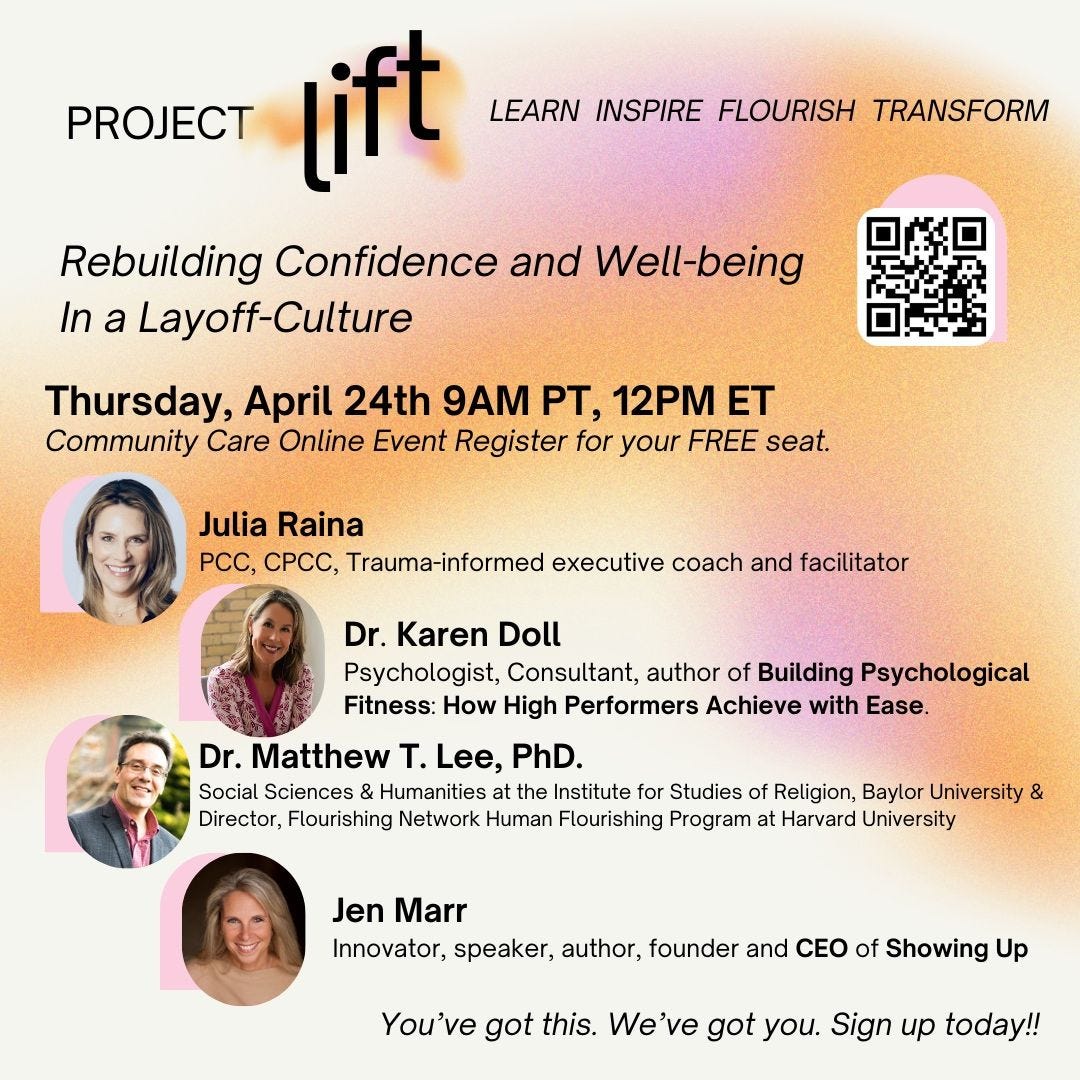

FREE Webinar: Project LIFT, Rebuilding Confidence and Mental Well-being in a Layoff-Culture

Optionality teams up with up-skilling and flourishing-at-work platform Aetheon to bring you a dynamic panel of mental health professionals, community builders, well-being experts, and resilience trainers who will help you understand the emotional impact of job loss, build greater resilience and mindfulness, and reframe setbacks.

Click the image for more information and to register:

Petit still performs on a wire. In a recent interview commemorating his most famous quest, he explained that high-wire walking is his “art".

When asked about his “relationship with fear” Petit said he has none when he embarks on his walks, but rather has a “child-like anticipation”.

“I am in control,” he said. “There is no fear.”

Even now, in his mid-70s he walks tightropes in his yard for hours a day, with as much ease and confidence as he had in his youth.

He explained, “I am probably more solid on the wire and more majestic that when I was a rebellious 18-year-old trying to prove things."

The high-wire is his tether to purpose.

I’ve been grappling with the paradox so many of us are experiencing now of pursuing purpose amidst uncertainty. Seeing so many friends losing jobs, or in a purgatorial place working diligently with one eye on the hatchet, I can understand the risk-averting choices they are making and have consistently made throughout their careers.

One founder I used to advise had an unspoken, and perhaps unwitting, strategy of generating the spectacle of a world-class high-wire walk but never actually performing one. She built just enough of a product and business to be pre-emptively acqui-hired. If there were no buyers before she needed more funding, she moved on. She’s did this multiple times, with one minimal win and multiple draws.

Another friend, with extensive experience growing and exiting companies but not starting them, was accustomed to high-wire walking but only with a “net” of substantial growth and a W2 beneath her. Now, with many netted walks behind her, she’s dedicated a considerable amount of time to coaching and investing in others early in their startup journey. She no longer needs to work, though perhaps she “walks” with other founders in the most uncertain stages of their growth to make up for the phantom first steps she never completed.

And another friend is deeply unhappy, perhaps even exploited, in her role. She has never felt the exhilaration of a high-wire, having applied for and held only three jobs in her 25-year career. While her hit rate is enviable, her life satisfaction isn’t. Uncertain times clamp around her differently; they prolong her suffering.

I can’t help but become more aware of the tightrope I’ve been walking for years now, but is thinning. I'm a 52-year old with a skillset most appreciated in white men in their 20s. Only now I’m intolerant of the exploitation endemic to being one of the few women at the tech-startup-grownups table: I don’t aim to please; I probably could say most things more diplomatically; and I don’t bludgeon myself in sanity-sacrificing loyalty for anyone because they write checks. All of these predispositions make me relatively unemployable by organizations that I used to turn to for security and sustenance, as toxic as they may have been.

And yet, I’m buoyed by the opportunities before me; early-stage companies with missions that let me finger paint, that seem like custom-built canvases for me. With people who inherently understand the challenges of tightrope walking.

I grapple with the tightrope, struggling to not waste time or lose money. I can hear the crowd below and can’t quite make out if they are cheering me on or screaming that I’m crazy. And there are loved ones at the starting point, holding onto the platform for dear life, both encouraging and imploring me, “OK, Jory, bravo for making it out so far, but there are bills to pay. Why don’t you strap on a carabiner and start making your way back?”

I think for a moment about what that means, to go back. I’ve done it before while waiting for purposeful, profitable serendipity. I hedge my bets by bingeing on junk work, drum up too much of it, and then get sick metabolizing it. Sure, I get a stomach ache, but at least I don't starve.

But interestingly, I can see from this place of most vulnerability, where I can feel the wind challenging, and more people watching me, and, perhaps, even expecting me to fall, that turning back is a false choice. It isn’t even a choice. There is only getting to the other side.

There are no wrong or right choices; there are investments. And as such, some investments do not pan out. But nothing pans out without investing. I have so painfully learned: There is no time in one’s career when there is pure certainty, or when we stop investing in our purpose.

And if our investments do not pan out we invest elsewhere. We invest differently. But we still invest.

And we don’t regret; we don’t look back.

And we certainly don’t look down.